The morning after election night 2016, I was standing between a steel post and a baby carriage in a crowded Orange Line train in Boston, staring at my phone, when a man turned to me and said: “Go back to your country.” He was white, bigger than I, and older, in his 40s, perhaps. The train was pulling into Back Bay Station, brakes shrieking. Moments earlier, the same man had been behind me, trying to elbow me out of his way, and I’d frowned at him over my shoulder, thinking, *Dude, there’s a baby carriage, do you mind?* Had I not been made aware of his presence before he’d spoken, his words might have left me speechless. But my irritation had been primed by his jostling, and I heard myself shoot back: “This *is* my country.” The doors slid open; he surged forward with the crowd. Within seconds, he had vanished into the bustle on the platform, leaving me to face alone the confused stares coming from all sides. People around us would have heard only my words, for he had spoken softly, almost in a murmur. It was as if he were just testing the waters of that new morning, trying to gauge what he could get away with on a crowded train in a liberal-leaning city. It was as if he had been working up to this moment for months, buoyed by the rallies and the tweet storms of the past year, events that had climaxed just hours earlier and whose full meaning I returned to eventually, with glazed eyes, processing it on my phone.

I’ve been wondering what made me declare, in the moment of our meeting, that this was my country, a claim I had never made before. When I introduce myself to strangers in the United States, I usually say something like: *I’m from India, from Bangalore; I’ve been here fifteen years; I came when I was eighteen, for college.* If they remark that I don’t speak with an accent, I’ll add that I lived in America for two years when I was a small child; that my father had a sabbatical in Dayton, Ohio, in the ’80s, and that I had learned to speak English there as a kindergartner and hence with an American accent; that we had returned to India when I was five years old, and never returned to the United States as a family. *I grew up in India*, I’ll insist, because I like to believe that I came to America on my own, as an adult in charge of my own decisions, that my kindergarten years in Ohio don’t count because I had no say then. The words *I came to America* carry for me the promise of self-discovery, the thrill of becoming the person one can be only when removed from the pressures and expectations of home.

A few years ago, when I was traveling on my own in Novosibirsk, Siberia, my host asked me if my husband was Indian. “No,” I said. “He’s American.” “Ah, but what does that mean?” the Siberian said with a touch of impatience. “Anybody can be American.” What he really wanted to know was whether my husband was of Indian origin, whether I had married within or outside of my culture. I was endeared by the impatience in my host’s voice, by his notion that the title “American” was so broad in its scope, so widely accessible, that to say someone was American was to say very little.

In Siberia, as in other far-flung places of the world, the idea that anybody can walk into America and become American might seem unremarkable. But within America, as I experienced on the Orange Line train that morning, the same morning that a Muslim woman riding a bus in Oregon was told by two white men that she was a terrorist and a school kid in Washington said aloud to his classmates, “If you weren’t born here, pack your bags,” the myth *Anybody can be American* can flip quickly to its converse: *Go back to your country.*

***

I had heard those words once before — fifteen years before, in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks. I was an undergraduate freshman then, having recently re-arrived from India on a student visa. As I made my way down Market Street in Philadelphia late one October night, accompanied by ten or so other women from my college, a man shouted those words at us from a passing car. Hearing them had little effect on me; their power was lessened by my ignorance of what a clichéd epithet it was and by my exhilaration at having arrived on my own in America. My friends and I had just been to a welcome party for international students. We’d munched cookies in a grand hall and listened to a dean make a speech, her voice booming from the loudspeakers, telling us all how lucky her university and others in Philadelphia were, how lucky *America* was, to have us bring our talents, our culture, and our voices from all over the world. During the dance, an inflatable, five-foot-high globe had been bounced into the hall for us to pass around.

Now, out on the street, someone in my group yelled “Fuck you” to the retreating car, and we repeated the words, tossing them into the night air as blithely as we had tossed that globe, feeling invincible in our numbers, our youth, and our celebrated status as citizens of the world.

***

When I came to America as a college student, I had no idea that I would stay after graduation. But I did stay. I became a fiction writer and a teacher, professions of my choosing. Had I returned to India, I would have struggled to give myself permission to write for several hours a day with no guarantee of publication, submerged in the goal-oriented, middle-class ether of my upbringing. Here in Boston, I’ve been able to labor freely at my craft. Each time I’ve asked for permission to remain in America, it has been granted. I am a permanent resident now, married to an American citizen. I benefit from the privileges offered to the educated and English-speaking and from the rights that people of color in this country have had to fight and die for. And if I do have to leave, I can return to India without fear of being killed or imprisoned, unlike the many thousands in this country, including the DREAMers, who have no such guarantee.

It is a bizarre strain of cruelty for a country as vast and wealthy as the United States to consider throwing out people who have grown up here and belong nowhere else, while at the same time allowing me — someone who arrived here by choice and not by force — to stay. Such a callous distinction suggests some sort of autoimmune disease, that the unhealed and accumulated wounds of America’s history have led the country to attack itself.

What I feel in common with the young unauthorized immigrants is their identity, forged in childhood, as Americans. While my memories of being a kindergartner in Dayton are vague, I know the teachers advised my parents to speak to me in English to help me pick up the language faster. I had come as an Indian kid, speaking only Tamil, and by the time we returned to India, I was an American kid, fluent in all things American: *Sesame Street*, *Curious George*, *Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood*, Crayola crayons, and Oreos. My Tamil had all but evaporated. I would regain a fraction of it over the course of the next thirteen years, in Bangalore, but I would never regain a sense of belonging in India. My Indian peers teased my American accent. *She’s foreign*, they said gleefully, and those words imprinted on my self-image, never to leave. Long after my American accent had faded, the sense of being a foreigner, of not belonging in India — a place that was supposed to be my home — remained. When I returned to America for college, I felt an unfamiliar sense of ease. My accent came hurrying back like a long-lost friend. *Anybody can be American*, the Siberian said.

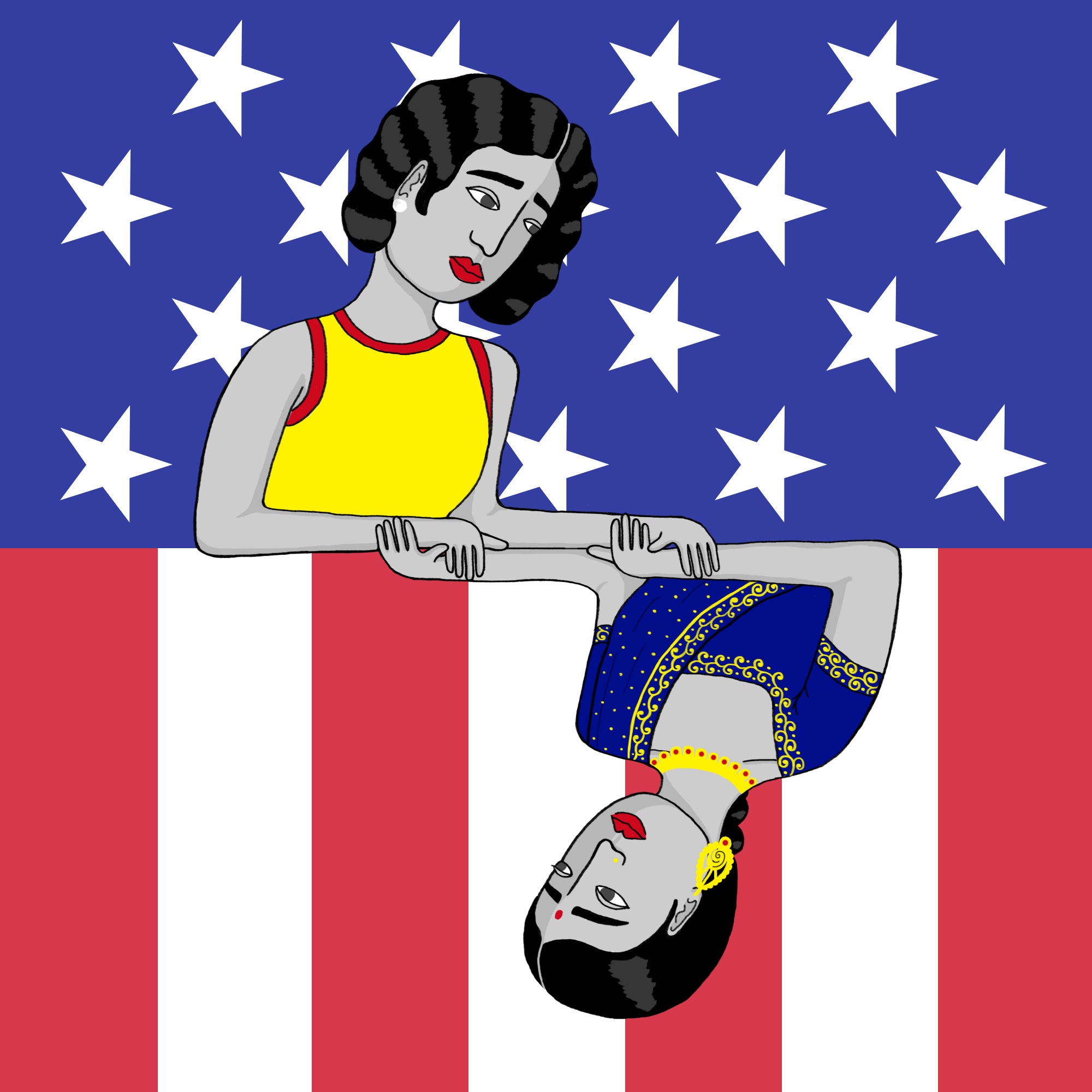

When I think back to how I was trapped on that train, with the steel post and the man at my back and the baby carriage in front of me, I think of how I am caught between the poles *Go back to your country* and *Anybody can be American*. Over the past sixteen years, my roots in my home country have grown looser while those in America feel deep. But sometimes I wonder if I have sunk my grip into a crumbling cliff face, if it is only a matter of time before I’m told by authorities larger than the man on the train that I am not welcome here.

My American roots are in my identity — the ease and confidence I have here that I never had in India. The fact that the words “This is my country” fell subconsciously from my lips rouses me as much as being told that I have no right to be here. I can no longer pretend I’m from somewhere else. America has taken me over, has taken over my reflexes, to the point that my unconscious believes I, like anybody, can be American.

*Shubha Sunder’s stories have appeared in places like* Crazyhorse, Michigan Quarterly Review, The Bangalore Review, *and* Narrative Magazine. *She is an associate fiction editor of* West Branch Magazine.