When I got off the plane at JFK after a year living with my biological dad in Texas, I saw my mom waiting for me. It was almost in that same spot, just a year before, that I had watched her walk away, shipping me off to live with a man who was a stranger to me. He had promised a life that my mom could never afford, and in her mind, she had paid her dues. It was his turn to deal with me. So off I went to live with the man she continuously told me was a loser so she was free to be with the current loser taking up space in her love life.

The next summer, I returned wearing the same outfit I had on when I left her, clothes that were now too young and ill-fitting. My dad made sure I didn’t take any of the clothes that he had bought me over the past year, allowing me to keep only two stuffed animals from my collection, holding all of my things hostage. The final two weeks with my dad were spent earning my keep: doing the dishes, cooking, sweeping, being shoved and kicked up the stairs to remind me that they needed vacuuming too. He was making me pay for my future betrayal while he still could.

And he was right. I had no plans to return after summer break. The only catch was asking my mom if I could stay back in New York with her. I didn’t want her to know I needed her. I couldn’t bear hearing her say no. On top of that, I had spent a year lying about how great my life with Dad was in an attempt to hurt her like she had hurt me. I lied about everything. I lied about driving to school in a Mercedes, about having friends who came from oil-money families, about Benetton shopping sprees. I even went so far as to say I’d gotten a pony. No lie was too outrageous when it came to letting her know how much better off I was without her.

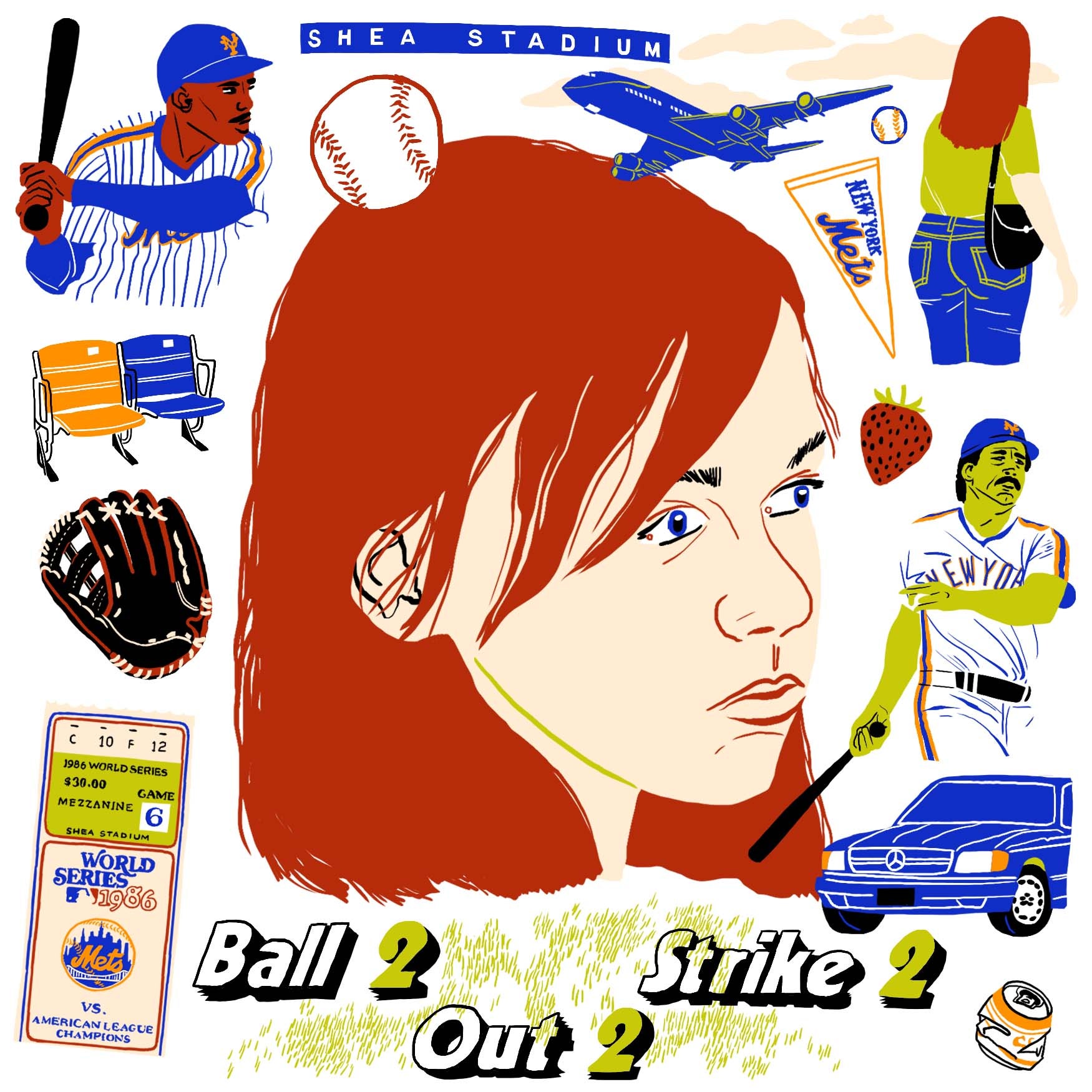

It was the summer of ’86 and my baseball team, the New York Mets, were on their way to achieving their own lofty mission — winning the World Series. I saw myself in them. We were both ragtag perennial losers. They blew games and seasons; I blew chances for something more. Too scared to be who I was and petrified people would find out where I came from. No one expected much from either of us, and the Mets felt like all I had. Relying on womanizing drunks and cokeheads had never served me well before, but these guys hurt only themselves. They weren’t the kind who hurt me. The kind who made me too scared to shower, so that I had to wash one body part at a time in the sink, never fully undressed, never risking my dad “accidentally” walking in on me naked.

The trajectories of my life and my team’s couldn’t have been more opposite. For them, everything was a drive toward the postseason, while I was dreading its approach. I was haunted by the previous summer, the last time I was unable to ask my mom to let me stay. Watching her purse bump her hip as she walked away from me at the airport. Willing her to turn around and give me a sign that I didn’t have to go. Each purse bump was like a slap in the face.

In New York that summer, I threw myself into avoidance. I constantly babysat so I could buy tickets to games and pay for the train to Shea Stadium. Surrounded by drunk fans in the cheap seats, I felt safe. They called me Strawberry because of my hair and the Darryl Strawberry jersey I wore. They protected me and yelled at the lazy men who would piss right in the stands. “Keep your dick in your pants. There’s a little girl here!” they’d say, as if I hadn’t seen that kind of thing a million times before. But every train ride home brought me closer to the end of summer. Last time I hadn’t said anything, but I hadn’t known what my life with Dad would be like then. Now I knew.

Mom was shocked when I finally asked. *What about the singing lessons? What about my rainbow canopy bed from the Spiegel catalog? What about the boyfriend who looked like Ralph Macchio?* She rattled off all the lies I told. She couldn’t understand why I didn’t want that life. I couldn’t understand why she didn’t want me. I still couldn’t tell her about all the bad things. That nothing I’d said about living with my dad was true. I felt like someone trapped in their own body, indicating they were still conscious with only their eyes, screaming internally for someone to see me.

She eventually said that she had to ask her boyfriend, which seemed worse than no. My fate was now in the hands of a man who once came out during Christmas wearing Rudolph-themed underwear, his soft penis barely filling out the snout.

I distracted myself with finding hidden meanings, once again looking for signs, tying every victory, every at bat, to my own situation. Twisting my logic of what things meant to fit the outcome I wanted. Lying awake in my bed every night, obsessing over stats, thinking about the Mets’ “magic number” — how many wins until they clinched. And what city would they be in? Their fate as uncertain as mine.

When Mom finally told me that I could stay, it was uneventful. There was no emotional, “very special episode” hug between us. *How do you thank your mom for keeping you?* My old anxiety about going back to live with my dad was replaced by an overwhelming sense of dread that my good luck had fucked up my team’s chances.

I went back to my Queens public school angry. Angry that everyone was the same and that I had to be different. Angry at the Phillies, the Phillie Phanatic, the flu that momentarily took down Keith Hernandez. Angry that things weren’t fair. Angry that I still so stupidly had hope that one day things would be better, clinging to that sliver of hope like it was a barely inflated lifeboat.

When the Mets finally made it to the World Series, I became more and more convinced that fate was a tease, bringing me to the brink of victory only to snatch it away. Game Six illustrated that perfectly. A ninth-inning rally by the Mets almost seemed cruel — to lose in extra innings would be unbearable. As the bottom of the tenth started, we were down by two. We scored again, but unlike the crowd at Shea Stadium, I refused to explode in cheers. It won’t hurt as much if you stop caring now. Didn’t they know?

Mookie Wilson was at bat, quickly getting to a 2-1 count, one strike away from the end. But an endless at bat of foul balls and a wild pitch tied up the game. Then Mookie hit a ground ball to first, the kind of easy out that ends innings. Only it didn’t. It went through Bill Buckner’s legs, escaping the clutch of the mitt just like I had escaped my dad. A moment so stunning, I wouldn’t have believed we had won if I hadn’t heard Vin Scully yelling at me, as if he were waking me from a bad dream. I knew then that we were safe. This was our year, and it was finally OK to cry. We would go on to win Game Seven two nights later, making the Mets the World Series champions. Purse bumps, loser boyfriends, and sink baths were replaced with the almost-painful invasion of joy. I let myself feel it. At least until the next season.

*Desi Jedeikin is a writer living in Los Angeles. She co-hosts the podcast* Hollywood Crime Scene.