My mother is a small woman, five two. She is strong but her bones are tiny and sometimes when I hug her I can feel her heart beat through her chest like the battering of an insect trapped in a lamp.

This town goes to bed very early but my mother does not. She doesn’t sleep well without my father and so she avoids sleep or she fakes it. She likes the town better at night. She likes things to be quiet. It is what she is used to.

There is a school on an island just off the coast a few hours south of here. It is a school for deaf children and, outside of the school’s building, there is nothing on the island but the founder’s pet cemetery. Horses, dogs, birds, and cats mostly. My mother grew up on this island. Both of her parents were deaf. Her father was the Plant and Property Man responsible for haying a small meadow, shoveling snow, mulching trees, repairing busted desks, washing the chalkboards at night, replacing rotten stairs and broken windows. My mother’s mother worked in administration typing health records, report cards, annual budgets in triplicate, and, twice, certified depositions on the accidental deaths of two children enrolled in the school, one drowned, one jumped.

Of the fifty to sixty people who lived on the island there were very few people who could hear things. My mother was one of them. She loved living on the island. She liked not talking and was annoyed that her parents sent her on a ferry every morning to a school for hearing people.

One surprising thing she told me about life on the island was that deaf people are actually very loud, especially deaf children. The reason is because they cannot hear to gauge the volume of their guttural emissions or excited shrieks. In fact my mother says she grew up accustomed to hearing her parents have sex because neither of them could hear the mighty creak their bed made and she was too embarrassed to tell them. So my mother was one of the few people on the island who could hear foghorns at night and seagulls in the morning, and being responsible for so much listening made her a very quiet person.

On the island my mother had a best friend named Marie. Marie was a very good lip reader because Marie had not been born deaf but lost her hearing swimming in a quarry that, after years, had filled with rain. Something was living in the water, Marie had told my mom and whatever it was, filled her ears and ruined her hearing with an infection. So Marie could talk a little bit, though my mother said Marie sounded like a donkey when she spoke. They’d run to the pet cemetery, and my mother couldn’t help but think that the animals were probably pricking up their ears down in their graves thinking that Marie was talking to them. She told Marie her theory. Marie brayed even louder. She wasn’t one to get offended because she sounded like a donkey. After that, the two of them always had it in their heads that they could talk to animals, even dead ones, and that was how they enjoyed themselves on the island.

More from Marie than from her parents, my mother tried to get to the heart of what it was like not to hear anything. She was trying to decide whether or not she wanted to be deaf herself. Marie signed to my mother that it wasn’t like what she might think. It wasn’t like a blank sheet of white paper because actually she heard things all the time. The sounds just came from inside rather than outside, like reading. But then that’s not really hearing, my mother answered, and Marie signed that what she meant was that deafness does not equal silence, which my mother understood. She liked to read a lot. Almost constantly. Then Marie said, braying in her way, “Also, it is wonderful.”

“It is?”

Marie read my mother’s lips and nodded yes.

“Why?”

“I can’t tell you. You have to be deaf to understand.”

“Give it to me,” my mother signed and put her ear up against Marie’s ear. They lifted their hats against the cold and aligned their heads like spoons. The cartilage of both their small ears was as plastic as suction cups and after making adjustments they created a tight seal like kissing lips between their ears. Marie closed her eyes, telling whatever deafened her that it was wanted next door and furthermore she didn’t want it. It wasn’t that wonderful at all. They stood that way, ear to ear both wishing something would happen. They stood that way long enough to convince themselves that this transfer wasn’t going to work, and then they were cold and walked back to the school and my mother heard the waves striking against the wooden pylons of their pier and Marie didn’t.

“After that, at night I would think about deafness in the way you might think of a beautiful man,” she told me. “I imagined its pockets and curves as though I could run my hand across deafness. I thought of it as a dark, heavy blanket that would pin me underneath it while I squirmed, which, at that time,” she said and winked, “was exactly what I was looking for.”

When her parents retired they moved back here, back to where my mother’s father had been born. Immediately my mother stood out as an oddball, a loner, a reader, a young woman who didn’t yell at her parents or carry on much. She thought she wanted to be a writer. She thought that she would one day move to New York City and pursue a career.

When she met my father she was still really good at being quiet. When she met him she realized how she had been collecting silence in a slender, delicate glass jar behind her ribcage. The bottle was not corked and so she always had to be very careful not to spill it. When she met him what happened was he took her out dancing and told her, “You make me feel like a pony.” She didn’t know what the hell that meant, but it made her damp inside like a flood, so the bottle broke and she didn’t care anymore as long as she could have him. All the good silent things she’d been saving up, like lights off in the distance at night or fog in the morning, ricocheted around her insides freed and she’d never felt so good. She went wild for him, taking on his habits, like drinking, driving with only one hand on the wheel, and other dangerous interests as though they were a new coat cut just for her. She tore about town like a match that had just realized it could burn down the entire village if it wanted to and she did.

Then I came along and soon all her ideas about writing and New York got away from her. My mother told me she would say, “Shhh,” and rest her head on my chest listening for my heart to beat or for my stomach to digest. “I didn’t want to be deaf anymore. I didn’t even want to be a writer anymore,” she told me. “In fact, I realized that the whole deaf/writer thing was just a place to hold the want I had had. This was what I had really wanted. A man to climb up on top of me and a baby to come out.”

It’s funny that she grew up not talking because now when she speaks she says things like this that other people might not say. It’s funny to hear her tell stories about how much she loved me as a baby because I think it has gotten harder for her to love me the older I get.

“You two saved me from a lonely, quiet life. You rescued me.”

But I say, “You’re the one who pulled me from the water.” And so she looks at me sideways again, tired by the way teenagers can lose their minds over things that make no sense to a woman her age.

My mother looks so young that sometimes people mistake us for sisters but she never tries to fool anyone. She doesn’t care if men think she is young or not. She doesn’t have much interest in men because she is still in love with my father even though he has been gone for eleven years.

My father was a dark, slender, and quiet man so that when he disappeared it seemed as if he just slipped away, a shard of stone or a splinter of wood. He drank a lot, so did my grandparents, both sets of them, so does most everyone who lives this far north. When my father disappeared I blamed his disappearance on his drinking. I was only eight at the time. Since then I have changed my mind.

Along the shore for hundreds of miles inland the water crops up as lakes and ponds as if to remind us it was under our feet all the time, traveling through underground tunnels, trying to make its way out to sea. My father told me that when he was young he used to try to make money by cutting blocks of ice from the lakes, storing it in sawdust and then selling it in the warmer months. His father and his grandfather had always done this for extra cash but my father had a bad time of it, working, as he was, in the time of electric refrigeration. Few people were enticed to buy dirty lake ice when they could go down to the grocery store and get a bag of fresh ice already clean and cubed.

“The lake ice was more beautiful than anything you will ever see. As clear,” he said and looked around for an adjective or noun to describe it, but he’d been drinking and the best he could come up with was, “as clear as clear plastic. And,” he continued, “huge. Chunks as big as any garbage can or,” again he looked around, “as big as the barrel of a man’s ribcage. In fact,” he told me whispering, leaning forward and tucking his can of beer on the floor beside his armchair, “I traded my ribcage for a chunk of ice instead.”

This explained a lot. From my father I got many recessive genes. Fair eyes, fair skin, and the mermaid part. The surrender places. I did not get a torso of ice though sometimes it feels that way, as if something solid that once was there melted now and still aches with the vacancy of him when it rains.

I ask my grandfather about the blocks of ice. I’d like to hear him describe the lakes, the ice, the ocean, and how they were when my father was young but he’s a man of few words with hearing difficulties.

“They melted,” he said.

“C’mon.”

“There you have your answer,” he says avoiding me, and so I wonder what else he knows but won’t say. I wonder if he also feels miles of dark water below him or if what my grandfather feels is just the same old pit of old people and their senility and he just can’t remember how the lakes, the ice, and the ocean used to look because he is old.

My parents captained a boat for my seventh birthday so we could pretend that we lived on an island for the day, and I remember my father saying, “Once when I was gill-netting for a man from Nova Scotia . . .” but then I can’t remember the rest of what he said about the man from Nova Scotia. I remember many phrases and sentences my father said to me like, “You let that screen door slam one more time and I’ll slam you,” or, “When you make Cream of Wheat you have to stir it the entire time or else you get clumps,” or, “I wish I’d invented the umbrella,” or, “I see your grandmother in you. Open your mouth. Let’s have a look. Is she in there?” But these phrases don’t even come close to making a complete portrait of him because mostly my father wasn’t good at talking. He was far better at sitting silently in his armchair, smoothing the back of his head and then taking a pull off a bottle of beer he kept between his thighs. He’d sit quietly, stirring a mixture of warm water and sugar to nurse back to health a sickly black fly or a disoriented mouse who’d been poisoned by the neighbors. These are the parts of him I find impossible to cut myself loose from. They are beautiful qualities. But beauty is heavy, and though I’m young I am getting tired from carrying around the bits and shreds of my father’s beauty.

My mother is still in love with him even though he’s been gone eleven years. She says, “Nothing has changed between your father and me. I just don’t see him as often.” As though he moved to Tallahassee or somewhere else way down south. She’ll say something like that and then ask me, “Why do you hang around with Jude? Why don’t you go find yourself a nice boyfriend?” But all I have to do is not answer her, and she’ll hear how ridiculous that sounds coming from her.

My mother married my father when she was twenty-seven. In those days, this far north, that was old to be getting married for the first time. On their first date my father surprised my mother. Outside the restaurant where they’d eaten he saw something black quickly crawling out of their way. Though he hated to do it, he loved animals, my father leapt, throwing his arm in front of my mother to protect her. With one foot, he squashed the creature. My mother was horrified. “I thought you wouldn’t like spiders,” he said. But when he lifted his foot it wasn’t a spider. It was a cricket.

“Crickets are good luck,” she said.

“You are right,” he said.

“You killed it,” she said getting to the point quickly the way she does.

“You are right,” he said again, shrinking. “I never kill spiders. I love spiders. I did it for you. I thought you might not like them.”

“No, I’m not like that,” she said. “I love spiders too. I love crickets even more but I love spiders too.” Soon after, they were married.

Sometimes if I am soaking in the tub or while I am trying to sleep I picture my father telling me about being a mermaid. I imagine things he might say to me if he were still around. Things like, “You might be living on dry land but you’re still subject to our laws,” and he’d mean the ocean’s laws. I would be relieved to hear this because it would give me comfort. I’d rather be subject to the ocean’s laws than the laws that apply to young girls trying to become women here on dry land. For example, many of the carnies at the amusement park are girls I grew up with. One of them has tattooed teardrops on her face, one tear for every year her boyfriend has been in prison. This doesn’t strike me as wise, as she is quite young. Though still, sometimes, I secretly wish I had teardrops tattooed on my face, as it seems to give the girl a purpose for now. When you are young, living in the north, sadness can make you feel like you have something to do. Sadness can be like a political cause almost or a religion or a drug habit. It is a lot of work to stay sad. I think of the carny girl’s teardrops and I can’t believe that is her purpose, but still I want a purpose so badly that I am envious even of that sad and ugly purpose she has. I suspect that she wants her boyfriend to stay in prison for a long time so that every year she can add another drop until they reach below the collar of her shirt and everyone who sees her will say, “My. There’s a sad girl.” She’s like an animal with her foot caught in a trap. In the wave of pain that rushes over her, she looks to the sky and she is braced by the color blue there. For a moment she imagines she can escape this ugly town and her imprisoned boyfriend, so she tries to use a knife on her bone above her ankle to free herself from the trap. Sadly, the knives they give out as amusement park prizes here don’t have the blade for any real cutting, and anyway she doesn’t have the money to move away.

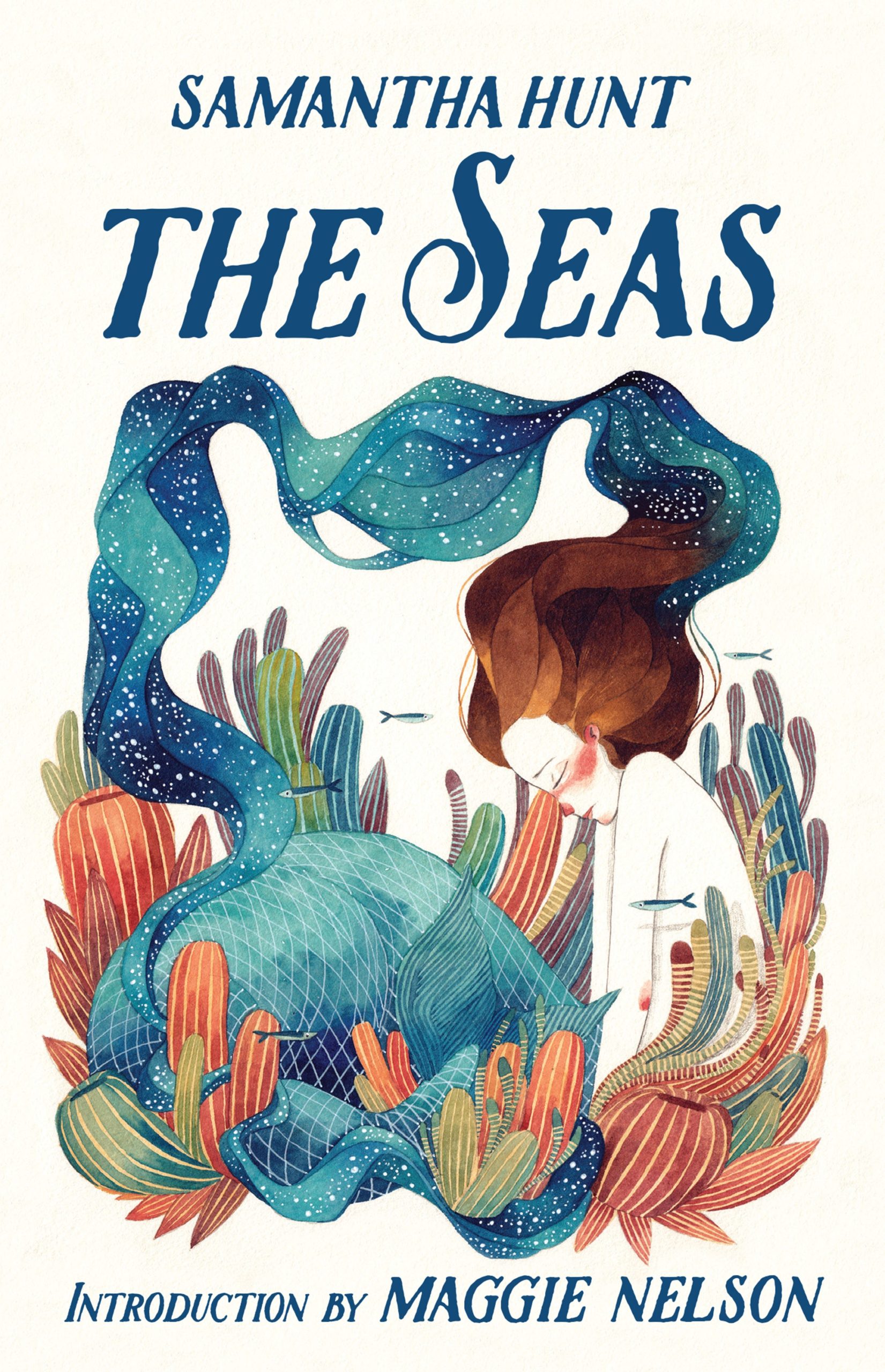

*Samantha Hunt’s debut novel, (1)* (1)*, won a National Book Foundation award for writers under thirty-five. She is also the author of* Mr. Splitfoot*, T*he Dark Dark: Stories*, and* The Invention of Everything Else*. In 2017 she received a Guggenheim Fellowship in Fiction. She currently teaches at Pratt Institute.*

1) (https://tinhouse.com/product/the-seas/)