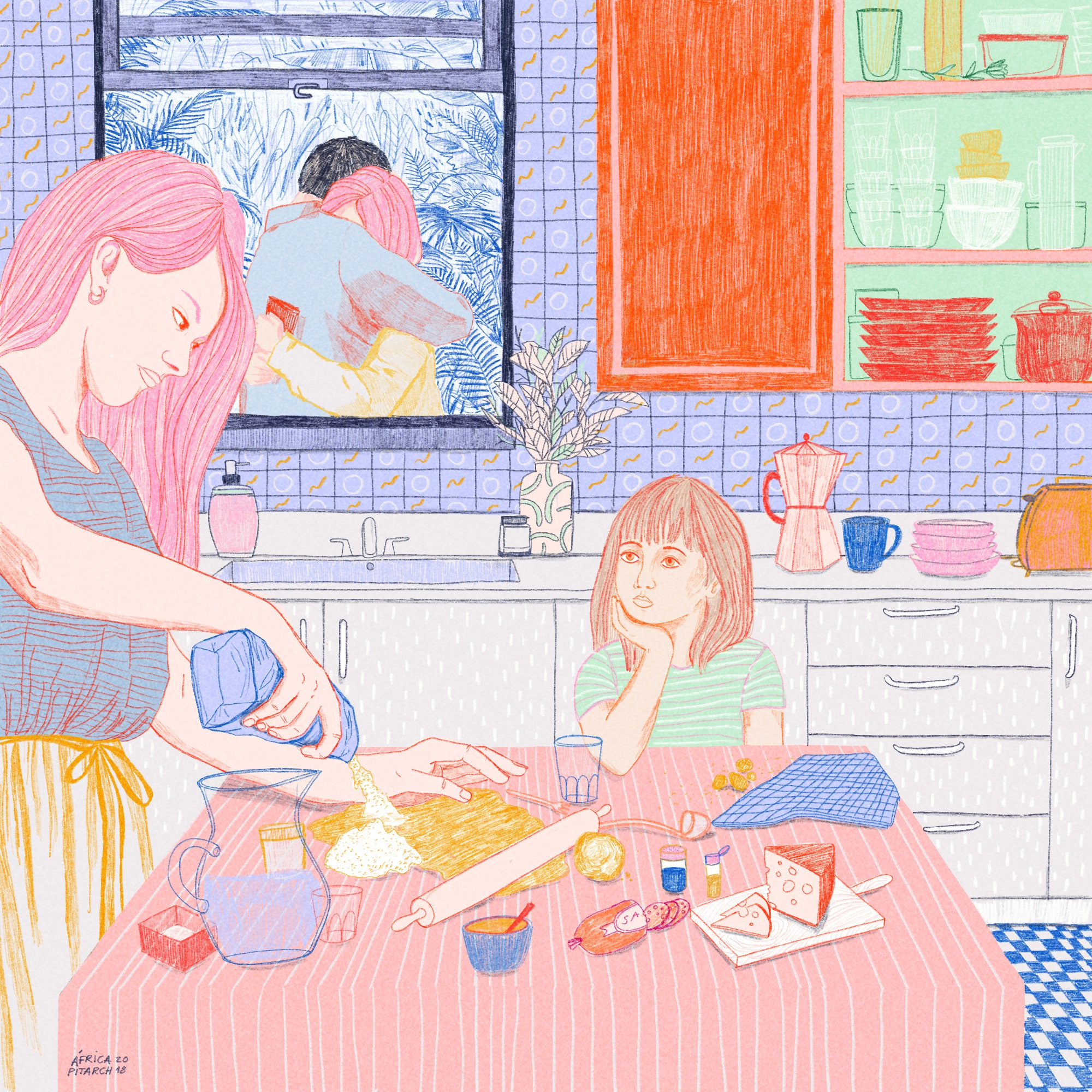

It was our usual Sunday morning. Coated in a dusting of flour, I pounded out pizza dough for dinner looking like Casper the Friendly Ghost. My husband, Dennis, had his head buried in a newspaper at the kitchen table. Noa, our daughter, who was eight at the time, kept snatching pieces of the sticky mixture to sculpt the little birds and flowers she insisted were essential to a successful recipe. That, and prattling on about how the best year of your life is when your age coincides with the day on which you were born. “Mommy, was it a great year when you were 26?” she asked.

I stopped, mid-knead. Dennis looked up at me. Time suddenly slowed.

*Twenty-six*. I was a reporter for the *Wall Street Journal* back then. Only a couple of years out of journalism school, I’d been assigned to cover Central America, whose regional wars made it one of the hottest international stories of the early 1980s. Being a foreign correspondent and working for a paper like the *Journal* was, for me, a dream existence. I could scarcely believe my good fortune.

And to top it all off, I’d fallen in love. Wildly. Madly. He was a veteran reporter for a West Coast newspaper, a divorcé with kids. I’d met him on the third day of my first foreign assignment in Costa Rica. Ours was a frenetic, breathless sort of romance, squeezed in among the wars and coups we had to cover for our respective papers. That we would rendezvous in such dangerous places — El Salvador, Nicaragua, Guatemala — only heightened the intoxication. We married less than a year after meeting, in an impromptu ceremony in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, between trips.

Ten months later, he was dead, blown to bits by a land mine on the Honduran-Nicaraguan border. And there I was: a bride at 25, a widow at 26.

“Actually, Noa, it wasn’t such a good year,” I said slowly, stalling for time. “In fact, it was the worst year of my life.” And I proceeded to recount the barest outline of my first marriage, tragic ending included.

Dead silence. “You were married before?” she finally said, her voice a mix of shock and hurt. “Why didn’t you ever tell me?”

Why, indeed. In the litany of possible parental sins, this was one of omission, not commission. I’d simply let the matter go too long. It’s like telling your kid about sex: best accomplished when she/he is very young and engrossed in, say, a compelling episode of *Sesame Street*. Reluctantly turning from the television screen, your offspring stares at you blankly after receiving the unsolicited information, says “OK,” then goes back to Big Bird. Done! The bare-bone facts are now firmly implanted in the child’s inner landscape, to be dredged up later — usually at crazily inappropriate moments — for further elucidation.

Not that I tried to hide any vestiges of my old life from Noa. I’d stayed in touch with my first husband’s children; Noa went with Dennis and me to my stepdaughter’s wedding. And she’d met my stepson’s children. But she never questioned their relationship to us, probably assuming they were just part of the crazy-quilt of extended kin stitched together from the divorces and remarriages and blended families that nowadays make genealogical charts resemble a New York City subway map.

I found it harder to tell her with each passing year. There were moments that I veered close to blurting out the truth, to coming clean with Noa, but I always choked. More maturity meant more questions. Like any parent, I wanted to shield my daughter from pain — a hard thing to do when having to recount the late-night phone call to my home in Mexico City that informed me of my first husband’s death. And the frantic attempts to get to Honduras to retrieve his remains before the government interred him there. And the interminable flight back to the States with his body stowed at my feet on the floor of a small plane. And the semi-falling-apart afterward when my editors, very thoughtfully, transferred me to Beirut — then in the throes of a brutal civil war — to recover.

To say nothing of fending off bizarre invitations from men like the putative Polish shipping agent who kept asking me to go on a picnic — because who wouldn’t want to sit outside on a blanket amid the debris of blown-up buildings and downed pylons, breathing the fresh scent of newly exploded shells and listening to the pleasant whistle of missiles flying overhead while grieving?

Nope, not a tale you want to tell your kid. Better just to bury it all.

And while we’re at it: When, exactly, post–Big Bird, is the right moment to try to make sense of the senseless to a child? Especially when it’s not something contemporary, demanding an immediate explanation. Part of my reluctance was surely to spare myself from having to relive the experience. Another part, magical thinking: *If I didn’t speak of it, the tragedy will never have happened*. At least not in Noa’s world.

It had taken me a long time to learn how to live with the pain of loss and lost love. It took me even longer to agree to marry Dennis, a diplomat I met when I was transferred back to the States. Terrified of chancing another marriage, I told Dennis I would gladly live with him in sin forever. But no wedding.

Until one day it occurred to me that, married or not, my love for him would always put me at risk of being hurt again. Because — and here comes the truism, obvious to most other sentient beings — life *is* all about risk. Everything from driving the interstate to eating fast food to bringing a child into our crazed world involves risk. Risk, and the belief (or even just the hope) that we can rise and love again after being beaten by the odds — precisely the sort of lessons I could/should have been imparting to my daughter.

“I’m truly sorry,” I said to Noa. “It’s a difficult subject to talk about, and I guess I didn’t know how.” And for the time being, we left it at that.

***

Fast-forward several years: another Sunday, another batch of pizza dough. It’s the summer that Noa is leaving, having finished high school and deferred her entrance to college. She’s going abroad to do a gap year of community service. She stands poised on the brink of her real life, and it’s sad and sweet and exciting all rolled into one. It’s also scary; proud as I am, I’m obviously worried about her heading off to parts unknown.

We’re trying to squeeze in as many of our little family’s sentimental rituals as possible before she leaves. After I’ve baked the pizza, Noa, Dennis, and I settle in to eat and watch television together: another Sunday tradition. The program is one of those ludicrously stylish British dramas whose writing and language never fail to captivate. But this particular episode contains a scene I didn’t see coming: a searing recitation by a woman whose life has been destroyed by the murder of a family member. Her poignant, almost unhinged accounting of the desolation she feels, of the utter futility of her post-loss existence, is a sucker punch to my heart. This hasn’t happened in years. I can barely breathe.

Afterward, Noa finds me in my bedroom. “Why are you crying?” she asks.

“I don’t know. Something about the woman’s story really hit home.”

“But you’re not that woman!” Noa protests. “You rebuilt your life. You fell in love again. You got married. You had me.”

Never underestimate the capacity of children to understand the universe — and to parse their parents’ place within it. Since our initial exchange on that other, long-ago Sunday, Noa has asked only the occasional question about my earlier life. We’ve talked of it in a mostly desultory fashion; she never seemed to want too many additional details. And I, following the sex-talk stratagem of responding only to what is queried, never volunteered superfluous information.

And yet, she got it. Completely. In the same way that, at a very young age — like all kids — she figured out which of her parents was the one to hit up for ice skates, which one to complain to about the math teacher. All those dim-witted years of avoiding the topic of my past, then tiptoeing around it once she found out? That was my problem, not hers. Somewhere along the way, she intuitively grasped the essential lesson: that with grit and resilience, anything is possible — even love. Especially love.

And, of course, pizza on Sundays.

*Lynda Schuster is a former foreign correspondent for the Wall Street Journal and the author of the memoir* (1).

1) (https://www.amazon.com/Dirty-Wars-Polished-Silver-Correspondent/dp/1612196349)