When I started acting as a kid in Pittsburgh, my mother insisted I list “Fan of Katharine Hepburn, Cole Porter, and William Shakespeare” under special skills. I still don’t see how those are skills, but it was true. I spent a lot of my free time watching movies from earlier decades, and one of my favorites was the 1939 classic *The Women*: it boasts an all-star cast of Joan Crawford, Rosalind Russell, and Joan Fontaine. The titular ladies are glamorous, witty, and catty, and the dialogue is endlessly quotable; Joan Crawford as the salesgirl temptress Crystal Allen purrs, “There’s a name for you ladies, but it isn’t used in high society … outside of a kennel.” Despite my affection for the film, I knew nothing about its screenwriter. It never occurred to me that the words were written by a woman.

It turns out the screenwriter, Anita Loos (who adapted Clare Boothe Luce’s play for the screen), was quite the powerhouse, and she started young. By 1925, she had already written hundreds of screenplays for stars like Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and Lillian Gish. Anita was born in 1888 in Sissons, California, to an itinerant newspaperman and theater producer, R. Beers Loos, and his more affluent wife, Minnie Smith. R. Beers was a charming, philandering, low-grade grifter, qualities to which Anita was drawn in the characters she wrote and the men she dated. Anita was a precocious, charming child and made her acting debut at age six in a stage production of the historical love story *Quo Vadis*.

After R. Beers moved the family to San Diego and began managing a movie theater, Anita became a devoted moviegoer. She noticed the best films were produced by Biograph Company and sent them a scenario under the name A. Loos, reportedly because male screenwriters were paid more than female ones. This was not an uncommon way for women to break into the movies back then. In that era, films were considered “low” entertainment, and many women, like Anita, wrote from home and submitted the writing by mail. According to the film historian and co-editor of *Anita Loos Rediscovered*, Cari Beauchamp, women wrote half the screenplays for produced films from 1912 to 1922.

Anita sold her first scenario at 24, although she later claimed to have been as young as 12. Her first produced scenario was 1913’s *The New York Hat*, directed by D.W. Griffith and starring Mary Pickford as a young girl who desires the titular, fashionable “New York” hat and Lionel Barrymore as the clergyman who buys it for her at the request of the girl’s dying mother. Despite her professional success, Anita was still living at home under her mother’s very watchful eye. A brief marriage to a man named Frank Pallma helped her get out of the house. She quipped, “In looking over the field, I separated the men from the boys and purposely chose a boy.”

Following her breakup with Frank, Anita moved to Los Angeles (with her mother in tow) to work for D.W. Griffith’s new company, Triangle Pictures, where she was known for her clever scenarios and subtitles. Griffith didn’t always appreciate Anita’s irreverent humor, but director John Emerson saw her value. He persuaded Griffith to produce some of Anita’s scenarios, and they had several hits with the actor Douglas Fairbanks.

Anita was in awe of the older (Emerson was 14 years her senior), taller (Anita was under five feet tall), more sophisticated Emerson. His background in the theater lent him prestige, and by 1912 he was a valued director at Triangle. Their nicknames for each other reveal the imbalance in power: She referred to him as Mr. E., and he called her Bug. Although Anita was apparently much more romantically interested in Mr. E. than he in Anita, they married in 1919.

Very early on in their relationship, he took co-screenwriting credits on her scripts, despite not writing a word. They had success after parting ways with Fairbanks, relocating to New York and writing several pictures for the Talmadge sisters, who were hugely successful silent-movie stars.

Emerson was less happy with Anita’s solo efforts. At first, Mr. E. tried to block the 1925 publication of Loos’s novel *Gentleman Prefer Blondes*, which is today her most famous and heralded work. Perhaps he wanted to block it because he found the subject matter unseemly or was jealous of her success. When that didn’t work, he asked her to include a dedication in the book: “To John Emerson, Except for whose encouragement and guidance this book would never have been written.” Her editor shortened it: “To John Emerson.” Once the book proved a massive commercial and critical success — Edith Wharton, James Joyce, and William Faulkner were all fans — John was quite happy to spend the profits. He and Anita lived in high style, often traveling to Europe. As Anita was fêted and celebrated, Emerson found ways to draw the attention back to himself, mainly through psychosomatic illnesses. Mr. E. often complained he was losing his voice, and after many visits to expensive clinics throughout Europe, one doctor pulled Anita aside to suggest a solution. Clearly, the ailment was in Emerson’s head, so what if the doctor put Mr. E. under anesthesia, scratched his vocal chords, and then after surgery presented Emerson with a jar of fake nodules? The scheme worked, and Emerson’s normal speaking voice returned.

Anita tolerated Emerson’s behavior, looked the other way in the face of his many infidelities (he requested one night a week off from their marriage), and didn’t seem to resent him terribly when he lost most of her money through a series of bad investments in foreign bonds during the Depression, partly because she felt her success was the cause of his unhappiness. Anita finally reached her breaking point in 1937 when Emerson, distraught at having lost her money, attempted to strangle Anita. She had Emerson committed to La Encinas Sanitarium, where he was diagnosed as manic depressive. Anita never divorced Mr. E., and in fact, the money he stole from her paid for his care for the remainder of his life.

After they went broke, Anita went back to work in Hollywood for MGM in 1931. Anita’s greatest champion at MGM was the executive Irving Thalberg. She wrote some successful films for Jean Harlow and Clark Gable and had a hit with the disaster pic *San Francisco* (1936). It was also during this era that she wrote my favorite, *The Women.* But after Thalberg’s untimely death at the age of 37, Anita struggled at MGM.

The studio system was difficult for writers as well as actors. Hollywood had changed greatly in her absence and not just because films were no longer silent. Movie moguls like Louis B. Mayer of MGM tightly controlled the studios, and the entire atmosphere was more corporate. Although Anita was valued for her wit and funny dialogue, she had very little discretion over her projects, as she was assigned and unassigned to film projects at the whims of executives. Eventually, Anita’s contract was not renewed by MGM, and she returned to New York and became a successful playwright.

She had a lot of false starts and disappointments in the theater as well. But the most inspiring things about Anita were her resilience and versatility. Whenever she faced a professional or financial setback, Anita wrote her way out. In the 1960s, she pivoted and remade her career as a memoirist. By then, there was a wave of nostalgia for the silent-movie era, and her books *A Girl Like I* (1966) and *Kiss Hollywood Good-by* (1974) recounted her memories of Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, D.W. Griffith, and other stars from the earliest days of filmmaking.

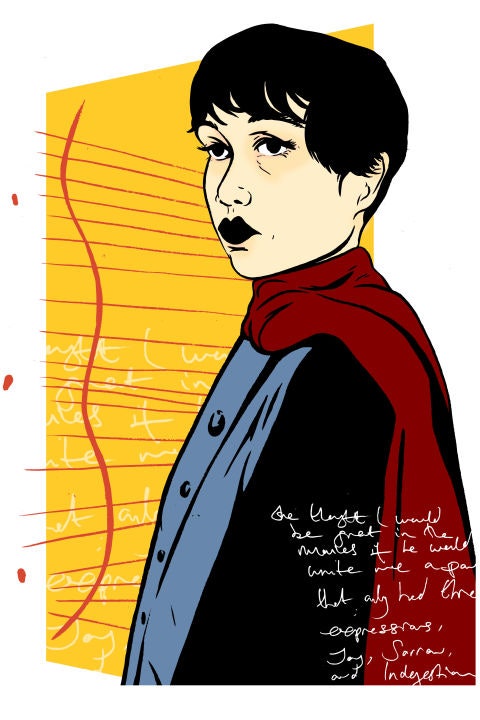

Although Anita was always self-deprecating about her talent, she was an incredibly hard worker, rising early every morning to write longhand on yellow legal pads. Though she’s no longer a household name, her influence is still felt. As Jenny McPhee states in her introduction to a 2014 reissue of *Gentlemen Prefer Blondes*, the book’s protagonist, Lorelei Lee, “skewers every possible power structure: politics, religion, class, society, culture, consumerism, psychoanalysis, Hollywood, even language itself.” That’s the reason why, in the 1980s, 60 years after the book’s publication and 30 years after the Marilyn Monroe film based on the novel became a smash, Madonna channeled Lorelei for her video “Material Girl.” The hashtag #DiamondsAreAGirlsBestFriend has upwards of 140,000 posts on Instagram today because Anita’s cleverness and insight remain evergreen.

*If you’re hungry for more, check out* Anita Loos Rediscovered*, edited by Cari Beauchamp and Anita’s niece Mary Anita Loos; watch* The Women*; and read the original* Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

*Gillian Jacobs is an actor (Netflix original series* Love*) and director (the documentary* The Queen of Code *on fivethirtyeight.com).*

***Correction, March 17, 2016:** The original version of this article misidentified the author of “The Women” as Clare Luce. She is Clare Boothe Luce.*