Ever since I met Vicky Featherstone, she has always made me nervous. She’s never shown me anything other than unlimited kindness and support, but, like with a crush, I often find myself struggling to hold her eye. I met her on her first day as the first-ever female artistic director of the Royal Court Theatre in London. I was in a writing group in the building when she came in to say hello. I knew nothing of her biography — knew nothing of her work with the late, iconic playwright Sarah Kane, or how she had set up the National Theatre of Scotland — but after hearing her say just a few words about her intended future for the theater, she excited me.

The Royal Court has a worldwide reputation for excellence in finding and producing the best new writing. But Vicky wanted to cast a wider net. She wanted the building to feel accessible to all.

I watched her open her first season in September 2013, beginning with Dennis Kelly’s Royal Court debut of *The Ritual Slaughter of Georg Mastromas*. It was a master class in storytelling. Vicky staged a wickedly bold and humorous production, taking the audience on a twisted Faustian trip. It was then that I understood that to be in Vicky’s presence is to be around someone who not only seems to be having the most fun in every room she inhabits but also is an exceptional talent who generously prioritizes both actor and script.

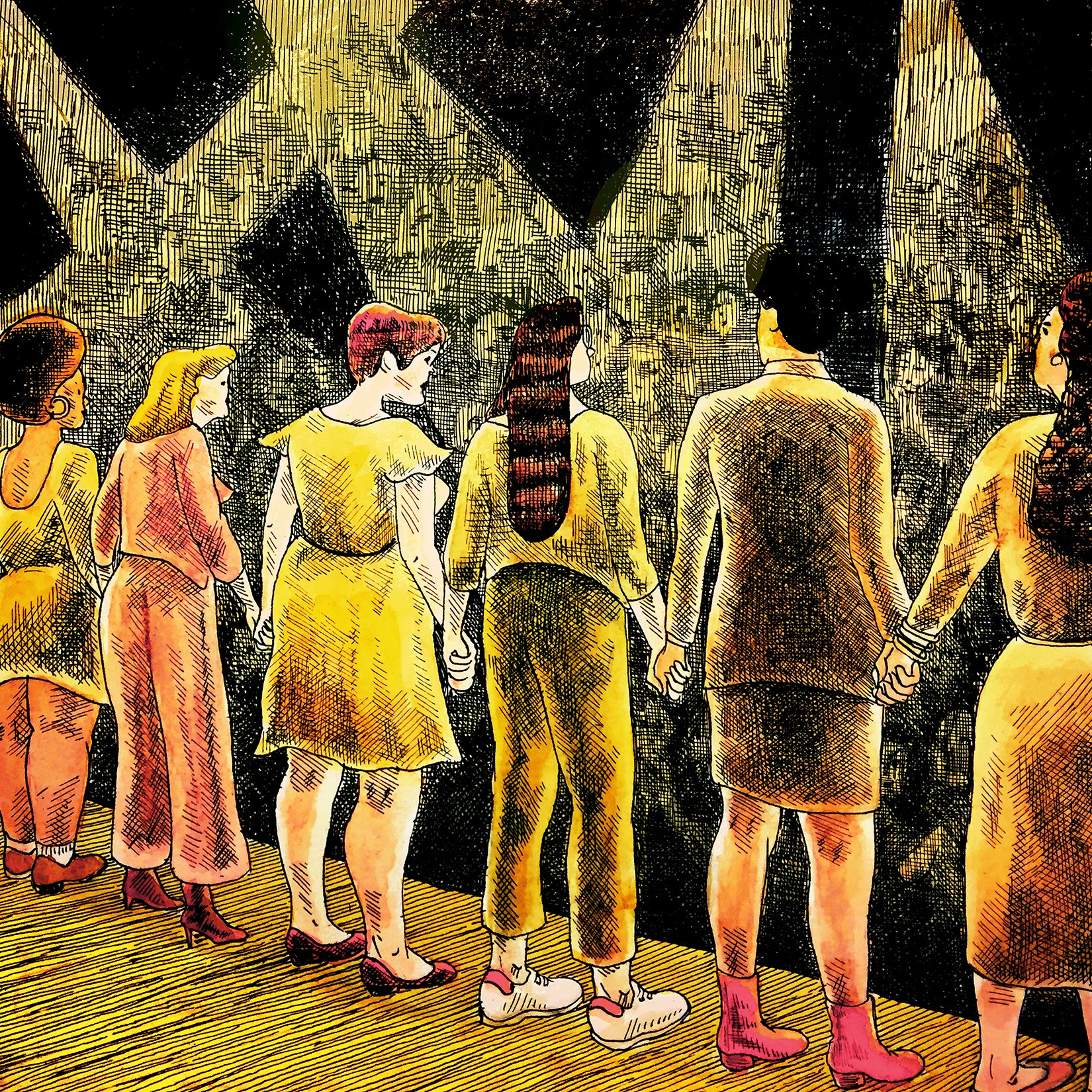

In the time Vicky has occupied the building, she has actively thrown open the doors to welcome completely different audiences and artists: Nonprofessional actors have performed in professionally run shows. We’ve seen teenagers from local colleges, who had never known what the building was, and children as young as six, writing and performing their own work. Even the programming of the main stage feels more varied than that of her predecessors, with Vicky ensuring that obvious successes like Jez Butterworth’s *The Ferryman* share the stage with the genius powerhouse that is Alice Birch’s Royal Court debut, *Anatomy of a Suicide*.

Vicky makes me want to be a better creative. The world in which she produces her work is joyous and safe; it’s one in which she’s reaching out both arms for people from all walks of life to come join her. Thanks to Vicky, the world of theater feels inclusive.

I sat down with Vicky in her office at the Royal Court Theatre on a bright and sunny day, overlooking Sloane Square. We talked about being women and taking your place in the world.

__Rachel De-lahay:__ Why theater?

__Vicky Featherstone:__ because I am addicted to that live relationship with the audience. I’m obsessed with empathy. That’s why I think theater is so extraordinary, because you come in as yourself and you experience something which isn’t you, isn’t your life.

__RD:__ Why this building?

__VF:__ I always got really bored of old plays. The classics have a place, but I’m really only interested in the voices of now and stories of now. I get so bored when people blow smoke up people’s arses for reinterpreting the classics for today, and I’m like, *Why aren’t we enabling a writer to write us a story that is now?*

__RD:__ Rather than just playing a rock song mid-way …

__VF:__ Yes. I love Bruce Springsteen, but is he relevant for now? No. Beyoncé is.

The Royal Court was created 60 years ago to be an opposition to the classics and the elite West End, to bring voices onto the stage that had never had that platform before. That’s what excites me about the Royal Court.

__RD:__ This is supposed to be this really provocative building. Why do you think there hasn’t been a female artistic director before now?

__VF:__ I think there’s something very interesting in our past about how women were not encouraged or given the platform to be more public beings and how we felt more at home in a private setting. If you think of dramatists at the time and you compare them to the Brontë sisters and Jane Austen and George Eliot and Virginia Woolf — women writing incredible, life-changing novels — the female dramatists at the time weren’t equivalent.

We see now how easy it is for women to be publicly trolled, much more than men — and I don’t just mean on Twitter, but shit pictures in the papers and all of that. It’s really hard to be a public woman. For me, there’s a thing about sticking your head above the parapet. I think after the 1960s, women started to stick their neck out a bit more about what they felt politically about art, about culture, about music. Then it became a more comfortable place to move into in a leadership role.

__RD:__ Is that why you went from acting to directing?

__VF:__ I went to Manchester University and did drama. I thought I would be an actor because I didn’t really know what else there was to do in theater.

I met people who were really brilliant actors, and I was like, *I’m all right, but I’m definitely not as good as Toby Jones*, for example. And then a friend of mine wrote a play, and he got so upset by the guy who was playing the lead that he said, “I’m going to have to play in it — will you direct it for me?” So I directed this play for him, and it all just clicked. I went, *Oh my god. That’s exactly what my role is*. I love nurturing people, encouraging people to find out what the story is and how to say it. the outside eyes is something that I really love.

__RD:__ As artistic director, do you get full say? Can you program whatever you want?

__VF:__ The board has a huge responsibility about employing the right person because, really, the artistic director can completely ruin a building if they want to.

I might want to further my career as a director, but then what I have to do is go: Are these plays by these writers the right thing for the Royal Court? For what other writers need to see? For how other writers need to be developed?

__RD:__ It became really clear to me, the importance of your moving into this building, when the * (1)* did a story about the women running London’s theaters. Quite naïvely, until then, I didn’t get why everyone kept asking me if I felt lucky to be writing as a woman. I realized that these doors have only just been opened for women, and I’m thinking, *Right, this is our time*. Do you feel a responsibility to make that happen?

__VF:__ It is our time, but it’s our time because that’s where we’ve all got to in our careers. We’ve all been working towards this.

One of the big things I felt when I left London in 2004 and went up to Scotland for ten years is that there’s nothing like the wonderful multiculturalism that we have in England. I was excited about coming back to run a theater in London and to have all those conversations, and it really shocked me how, in ten years, it felt like London had actually gone backward. I rang up Kwame , who was living in Baltimore, and I said, “I thought I would come back to a tidal wave of change, and actually it’s all just trickled on a bit.” He was like, “Everybody got tired and we never reached the tipping point. People stopped having the conversation.” And that really taught me something: Until everybody in power looks different to how they look now, we have to keep having the same conversations. That’s when the change happens.

*This interview has been edited and condensed.*

*Rachel De-lahay is a playwright under commission for the Royal Court Theatre.*

1) (http://www.standard.co.uk/goingout/theatre/centre-stage-the-women-in-charge-of-theatreland-8901451.html)