When I was nine, my fourth-grade teacher gave an unconventional assignment to my class of rowdy public-school Brooklynites: create your own business. This was, obviously, an aspirational business, but a business nonetheless. We were instructed to create a business model, business cards, basically anything having the word _business_ in front of it.

Although I was shy, I was a hungry and eager student, and I immediately homed in on the business I would create: an all-female construction company called Big Women. I called lumberyards and got quotes and put together some ramshackle excuse for a business model. I still to this day have the business card I drew on construction paper. It reads: “BIG WOMEN CONSTRUCTION … _There’s no job too big, for Big Women.”_

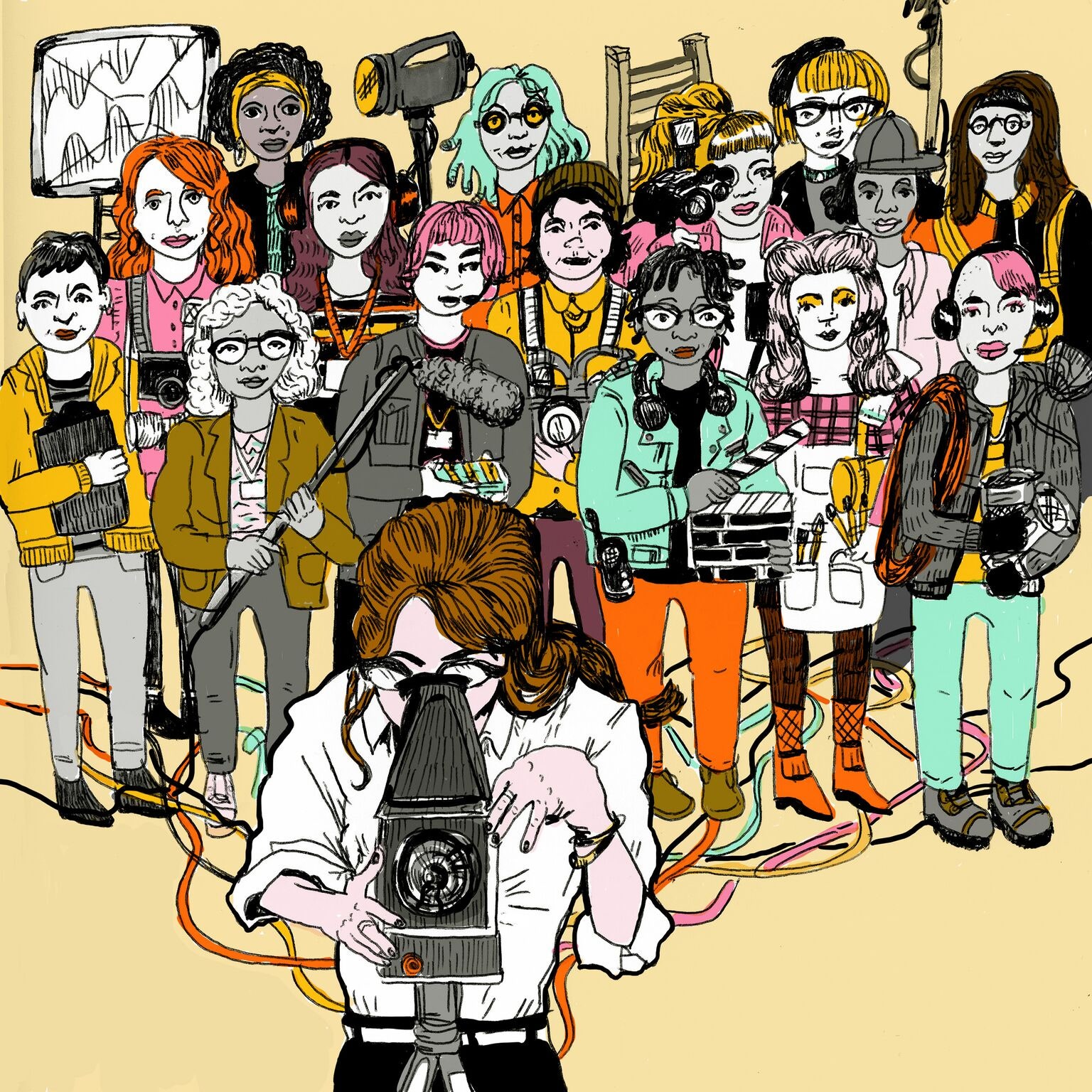

Last summer, I directed my first feature film, called _Band Aid,_ which is the story of a couple who, in a last-ditch effort to save their marriage, decide to turn all their fights into songs and start a band. I had written and produced films that I had acted in before, but this was undeniably new territory. I knew it would require leadership skills that I had not yet put to use; that fine balance of encouragement and discipline to achieve a singular vision. It would also offer an opportunity to build a community from scratch. With the same instinctual clarity upon which I had drawn at age nine, I knew what I would set out to do: hire an all-female production crew.

My mother, a video artist, founded an all-female film collective in Vancouver in the early ’70s called Reel Feelings. In her house, there is a framed black-and-white photo of the collective in 1976: nine women, varying in age, each wearing a wedding dress, standing on a beach.

To give you a little insight into my mother, when my father first asked her out, she gave him a list of books, including Germaine Greer’s _The Female Eunuch_ and Simone de Beauvoir’s _The Second Sex_, and told him to come back only once he had read them. My mother is a feminist of the highest order, and she raised me to look at the world with a particular focus on gender inequity.

Throughout my childhood, she towed me along to protests (my earliest protest memory is, at age ten, calling for an end to rape in the former Yugoslavia) and to meetings at the Women’s Action Coalition. And each year, when we would visit our family in Calgary for Passover, she would have me read a supplemental passage from her feminist Haggadah, outlining the ten plagues for women, which was inevitably followed by my great-uncle storming out of the room in a fury.

> I wanted to ensure that we made a quality film, and I had my own fears around the ramifications of, in a few instances, hiring a crew member who might have less experience on her résumé than her male counterpart.

As an actress, I have been all too aware of the underrepresentation of women behind the camera. To give you an example, outside of _Band Aid,_ I have acted in 40 productions and, out of those 40, I have worked with only three female cinematographers. My personal experience in witnessing this jaw-dropping ratio is mirrored by current statistics. At present, the numbers are staggering.

According to the (1) at San Diego State University, in 2014, 85 percent of films had no female directors, 80 percent had no female writers, 33 percent had no female producers, 78 percent had no female editors, and 92 percent had no female cinematographers.

In 2016, (2) was repeated, only to reveal that despite more public attention to women’s underrepresentation on film sets, the numbers had gotten worse. Thirty-four percent of films had no female producers, 79 percent lacked a female editor, and 96 percent didn’t have a female cinematographer.

And that doesn’t even mention female crew members below the line. I can only imagine the statistics when it comes to women, particularly in camera and electric departments. In hiring an all-female crew, I was given insight into the vicious cycle that prevents more women from being given opportunities on film crews. Even some of the female department heads I interviewed wanted to hire male crew members in their departments based on prior working relationships and/or levels of experience. I was faced, day after day, with roadblocks in achieving my vision. I too, of course, wanted to ensure that we made a quality film, and I had my own fears around the ramifications of, in a few instances, hiring a crew member who might have less experience on her résumé than her male counterpart.

But I also relied on an understanding that in certain departments on film crews, this logic is precisely what limits female crew members from gaining the experience necessary to open more doors on productions that are larger in both budget and scale.

Let me be clear: there were plenty of women on my set who had ample experience. But in those instances where I was forced to take a risk, I chose to. Because if not me, then who? And if not now, then when?

“But why _all_ women, rather than just making sure to hire a number of women in key positions?” many have asked. Precisely because of the patterns I had witnessed firsthand. The decks are stacked too weightily against us. In order to effect change, I felt I had to subvert the paradigm completely.

What ensued was the most creatively fulfilling experience of my life. A beautiful trait that so many women seem to share is an inherent anticipation of others’ needs. On a film set, this is worth its weight in gold. There was an interdepartmental generosity that I had yet to experience to this degree on previous sets. There was a kindness, a sense of grace and humility, that was effortlessly contagious.

This was a community of intrepid women, each inspired by the other, and each the mistress of her own vision. And yet the synchronicity and support was so symbiotic. On what could have easily been a hectic and harried set, our work was instead fueled by a love for our craft. Even more so, each day was a tiny revolution, and the spark of harnessing our power together, as none of us had ever done before, was electric.

_Zoe Lister-Jones is an actress, writer, producer, and director whose debut feature,_ Band Aid, _will be released theatrically on June 2._

1) (http://variety.com/t/center-for-the-study-of-women-in-television-and-film/)

2) (http://variety.com/2017/film/news/female-directors-hollywood-diversity-1201958694/)