Ten years ago I was in Mumbai with a friend I’ve since fallen out with. We were visiting another friend whom, as time has passed, I’ve also lost touch with. The three of us were there for New Year’s, and my friend and I—the one I fell out with—were traveling back to Kolkata by train once the trip was over, and then back to New York shortly after. At first, the idea of Mumbai was exciting. Visiting friends in foreign cities usually is. _Isn’t this crazy?!_ we’ll say upon reuniting. *Completely wild*, we’ll nod. The extreme familiar—a close friendship—reoriented by the extreme unfamiliar is usually a formula for fun. All the qualities of a new experience in the company of someone who lessens the overstimulation sometimes brought on by new experiences. This is why we laud people who make good travel companions. We value that mix of curiosity, of limit- ing impatience for the trip’s duration, of being responsive, even-tempered, but also willing to skip the museums and spend whatever money you have left on day drinks and aimless walking.

But in Mumbai, I remember drinking too much vodka and feeling restless. Like I couldn’t figure out why I was there. Like I was meant to be having fun—so much of it—that as a reaction, my anticipation had soured. I was in possession of all this freedom, traveling with a friend, visiting another friend, and yet, I felt hollow. Looking out an apartment window, standing on a balcony, returning to my book, barely reading, thinking of perhaps sightseeing, not knowing where to start. Waking up early and badly wishing for the chatter only a family can provide. That nothing-talk that grows lively for no reason. Ten years ago was too young to know friends who chatted in the morning. It still might be.

But one morning I was given a task. My mother called and asked, since I was the only immediate family from Canada in Mumbai at the time, if I’d visit my cousin’s husband’s mother who was recovering in the hospital. She had undergone heart surgery. I was thrilled. Something to do. A destination. I could leave my friends, the vodka, the lazing around, and arrive somewhere. I got dressed, decided to wear a pair of dangly earrings, and grabbed a shawl my mother had loaned me for the trip.

Downstairs, my friend waved over an auto-rickshaw and in Hindi instructed the driver where to go. I under- stood none of what he said, but smiled, climbed in, and stared at the map I’d drawn that now looked like nothing at all. A few lines, a turn I’d emphasized by going over it a few times with my pen, some more lines, a big loop. The scribble had made more sense moments ago, but now that I was in the auto-rickshaw, among life as it zipped past me—two wedding processions; daylight waning; immea- surable traffic—I hoped the driver knew where he was going.

> The more I pronounced the words, the more the words lost all of their meaning. Say anything too much, and soon language becomes pummeled nothing.

An hour went by. We’d stopped twice for directions. I showed anyone willing to help, my map—the lines, the turn, the more lines, the big loop. I said “Heart Hospital” over and over. _Heart Hospital!_ Of course that wasn’t the name of the hospital. It was called the Asian Heart Institute. But somewhere along the ride, the rickshaw driver started saying heart hospital and so I started saying heart hospital. Whenever someone giving directions would nod, I would nod. He nods. I nod. And so on. But shared nodding in a country where you don’t speak the language is, I learned, the same as saying, _Yes, yes, yes_. But what were we agreeing on? Was I simply trying to keep the mood light and not look too confused? “HEART HOSPITAL,” I enunciated. The more I pronounced the words, the more the words lost all of their meaning. Say anything too much, and soon language becomes pummeled nothing. Totally estranging, inadequate, and without substitute. Your tongue may as well be numb.

By the time it got dark, we had driven on all kinds of roads. The driver’s handlebar steering revved loudly as if accepting a new challenge each time we curved around and inched between cars. Oddly enough, I never grew anxious. A deep calm nestled inside of me like my nerves were newly insulated. Like when a dog chooses my lap to curl up on. Like when a sweater is too long in the arms. Like when nobody is speaking and nobody feels pressed to.

Anything could be just outside this doorless, trembling auto-rickshaw. The unreal, even, like raging water, bare desert for miles—and it wouldn’t matter. I was disoriented yet deaf to concern because I only experience the candied tang of what’s imminent—the possibility of drawing near— when I am truly lost. When hope is a weak vital sign. A low ticking. A glowbug.

Maybe I would never arrive at the heart hospital. Maybe it didn’t exist. Maybe I was lost in Mumbai. The trip had felt like nothing up until now. As far as I was concerned, failing to find something was greater than having nothing to look for. So I let go. I leaned back against my vinyl seat. I closed my eyes. I felt the road’s bumps—a replenishing, gentle shock each time. I felt the abrupt, crass smoothness of highway. I felt the night’s breeze, my own breathing, and sounds approaching, and horns passing. I heard unspecified purring like a score of whispered secrets, sped up and looping, and just a bit sinister. More so than daytime noises, nighttime noises wreathe.

With my eyes closed, I felt like I was flying. Arbitrary images popped into my mind as if what screens inside my eyelids is half haunted and clipped of story. Those tousled and nearly unaccounted-for impressions. Those observations that go nowhere yet enrich my memory—incongruous, random, and without incident, like found footage. Like the sheared memory of Christmases; the topography of someone I love’s palm; roof tar sticking to my shoe; a skinny cat’s rib cage; the rubbery satisfaction of yanking a single blade of grass from its root; the sound of someone setting a table for lunch in the garden and those intervals of silence where she looks up at the sky to weigh the threat of dark clouds and how fast they’re moving, and in looking up, she wickedly obscures who has more power—the incoming storm or the woman bargaining with it by placing cloth napkins as winds pick up.

> Is there anything better, more truthful and sublime than what cannot be communicated? The marvelous, hard-to- spell-out convenience of what’s indefinite.

Even more indiscriminate thoughts collage. Like my irrational fears: dryer lint, the void that hollows a spiral staircase, or the several ways I feel illegitimate whenever I allow myself some latitude. Or feeling somehow fidgety when there’s unexpected legroom on a plane; the ugly manner in which my face warps when big tears are about to overwhelm me, and how repressing them means deforming my cheeks and chin and forehead as though a leech is swimming frantic beneath my skin. Or the power that composes me when I walk down the aisle of a moving train. Or the coppery taste of blood; the slippery touch of cherry seeds; signing my name on condensation; the novelty of a round window; how little I know about birds. How the string section of an orchestra appears hypnotized, far more than the brass and woodwind; how at the grocery store, spotting the bottom hem of a woman’s nightgown under her raincoat feels classified. Or how awkward it is to be in the company of a friend who’s expressed to me that I’ve been inconsiderate and self-absorbed, and how attempting to mend my pattern is graceless, pinching, and worse, feels false. How being hard on myself is, oddly, a lazy system for letting myself off the hook. How sometimes I imagine hubcaps spinning off the wheels of cars and slicing me in two. How a coral shirt I rarely wear compels my friends to argue whether the shirt is _more salmon_ than coral, and even if the difference is slight, sometimes it’s nice to hear voices I admire boom emphatically over dumb, trifling things.

The memory of peering into my cousin Samantha’s bedroom surfaces. I was small, no older than ten, and I spotted a biography of Marilyn Monroe tossed beside a pair of black Dr. Martens boots, and Samantha caught me looking and slammed the door, and instantly Marilyn Monroe and Dr. Martens were the most forbidden. Or my mother’s crooked teeth. Fanged and disobedient. Crowding her mouth like concertgoers front row, pushed up against the stage. They are my favorite set of teeth because when my mother smiles her teeth resist any notion that happiness is an upshot of perfection. Her smile is chaotic. Teeming, toppling, and lovely.

“Madam . . . madam.”

I’d closed my eyes just long enough to have dozed off.

“Madam,” the driver said again. “Museum.”

I slowly came to and felt my mascara unstick between my lashes.

“Museum, madam.”

“Museum?” I asked.

“Heart museum.”

_Oh_ _no_, I thought. He’d brought me to a museum in the middle of the night. I looked out and saw nothing.

The driver pointed up ahead. “Heart museum.”

This couldn’t be right. “No, no.” I shook my head. “Hospital. _Heart hospital_.”

“Heart museum,” he repeated.

A museum? At night? I lifted my chin, suggesting we should drive up the road some more.

The driver was now smiling as we inched closer. As the rickshaw pulled up to the front, I peered out and saw what looked like a very fancy hospital. That’s how I remember it at least.

“Heart museum, madam,” he said once more.

I nodded, thanked and paid the driver, and walked toward the entrance. It had become chilly and I was grateful to have brought the shawl with me. Quietly moved by the rickshaw driver’s construal of this large, looming building, I climbed the stairs. Even though this was a hospital and in visiting family I was only doing my daughterly duty, his characterization of “Heart Museum” recuperated in me what I was so longing for: a sense of arrival. The words “Heart Museum,” like a figurative place; a vault where memories shimmer, fall dark, are cut loose, and unexpectedly flare up when you most need them to. The words “Heart Museum,” like an experiment; twitchy, sad, parceled, soulful, like Arthur Russell. The words “Heart Museum”: a meaning archive; a parent’s medicine cabinet with expired sunscreen and old Band-Aids; the contents of a care package; a hideout for mind and spirit; mausoleum-_like_. The words “Heart Museum,” like the essence of a word from another language for which English has no word. Because is there anything better, more truthful and sublime than what cannot be communicated? The marvelous, hard-to- spell-out convenience of what’s indefinite.

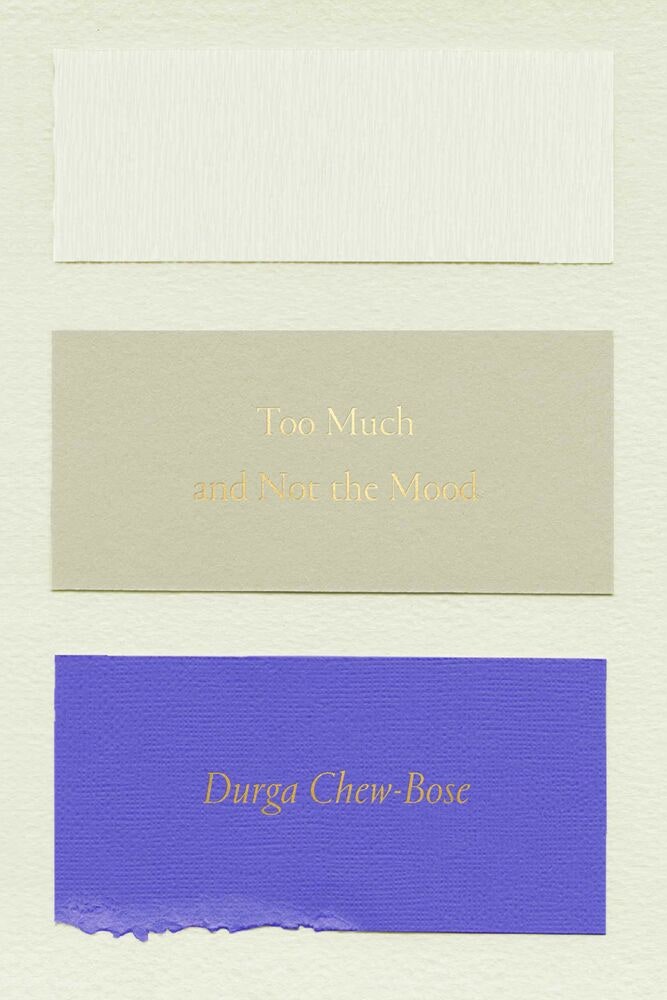

_Excerpted from_ (1) _by Durga Chew-Bose. Copyright © 2017 by _Durga Chew-Bose_. Published by FSG Originals. All rights reserved._

1) (https://www.amazon.com/Too-Much-Not-Mood-Essays/dp/0374535957)